That’s certainly what Wall Street and the financial media want and need you to believe, because active management is the winning strategy for them (although it’s the losing one for you).

Before addressing the issue, it’s important to understand that even if a majority of investors indexed (and we are nowhere near that scenario), active management remains a negative-sum game after expenses (John Bogle’s Costs Matter Hypothesis). And active investors would still be the ones setting market prices.

We’ll begin by observing that, according to Morningstar, index funds account for only about 15% of total equity holdings by market capitalization. It’s hard to argue that indexing has gotten too big when 85% of mutual fund assets are still engaged in active investment strategies. We now turn to a second important issue.

The Pool of Victims to Exploit Is Shrinking

Dividing the market into two types of participants, individual and institutional, we know that many consider individual investors the “dumb” money. In other words, they’re the victims that institutional investors seek to exploit. The research shows that, on average, the stocks individual investors purchase go on to underperform and the stocks they sell go on to outperform. Since someone must be on the other side of the trade, we know it must be the institutional investors. And that’s what the evidence shows. Institutional investors do exhibit stock-picking skills. Unfortunately, after the expense of this effort, on average, the alpha from stock-picking skill turns negative. Its expense far exceeds the ability of active managers to generate alpha from picking stocks.

Understanding who these victims are is important, because the pool of victims active managers need to exploit has been rapidly shrinking. At the end of World War II, households held more than 90% of U.S. corporate equity. By 1980, U.S. corporate equity held by households had fallen to 48%. By 2008, it had dropped to about 20%.

Making matters worse, the competition seeking to exploit pricing mistakes has dramatically increased. There are now more than 7,500 mutual funds, according to the Investment Company Institute. That is 14 times more mutual funds than there were in 1979. Increased competition for a limited amount of alpha reduces the ability of any given fund to outperform.

In the zero-sum game (negative sum after costs) that institutional investors are playing, the other side of the trade is highly likely to be another institutional investor. Only one of the two, however, can be on the right side of a transaction.

Is the Trend to Indexing Making the Market Less Efficient?

Is the Market Becoming Less Informationally Efficient?

As Vanguard’s Chris Philips noted, “Arguably more people than ever have more access than ever to information and technology. This suggests that market efficiency should be better now than ever before regardless of how much the market is using index strategies.”

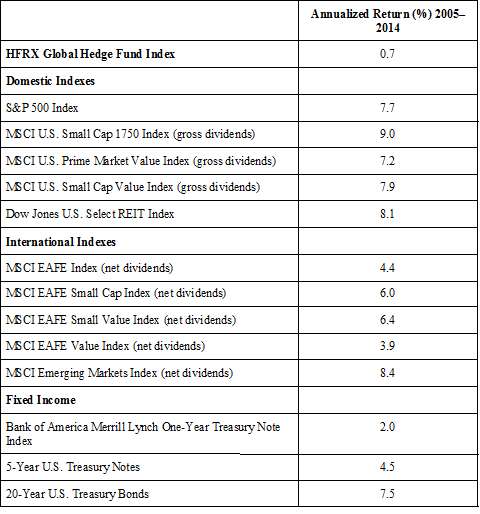

As evidence that the markets aren’t becoming less efficient, just consider the returns to hedge fund investors. The performance of hedge funds for the last ten calendar years has been so poor that, in returning just 0.7% per year, these “masters of the universe” have managed to underperform every major asset class, including virtually riskless one-year Treasuries.

The Good News

This trend toward lower expenses is making passive investing even more of a winner’s game. That in turn is contributing to a vicious circle for active investors. Lower costs are helping drive more investors to become passive, further shrinking the pool of victims that can be exploited and raising the hurdles for the generation of alpha. Since investors abandoning active management aren’t likely to be the ones who have been able to generate alpha, the remaining competition is only likely to get tougher and tougher over time.

The bottom line is that there’s nothing that would lead me to believe the trend toward indexing – and passive investing in general – is going to slow down. The trend away from active investing, on the other hand, is as inexorable as the tides.