Sales Loads

Front-End Loads

Front-end loads are imposed on the investor when they make a purchase of shares. It can be thought of as a commission fee, one that you would normally pay in your brokerage account when opening up a new position. The fee is usually percentage-based and will be taken away up front, lessening the amount of money you can invest in said asset.

For example, if you wanted to invest $1,000 in a fund with a 5% front-end load, $50 would be immediately paid (usually to a broker) while the remaining $950 is invested in the product. The SEC does not limit sales loads, but the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) caps them at 8.5%. This means that you will never pay a front-end fee in excess of 8.5% of your investment [see also 7 Questions to Ask When Buying a Mutual Fund].

Back-End Loads

Back-end loads (also known as deferred sales loads) are a bit trickier as there are a few attributes that go into calculating these fees. For a basic definition, back-end loads are fees that are paid when selling shares of a fund you already own. When it comes to calculating the fee, however, most funds only use your initial investment amount.

So, let’s say you invested $1,000 in a mutual fund that has a 5% back-end load. Now let’s assume that when you want to sell your shares, your position is worth $1,500. Most funds will apply the 5% back-end load to the lesser of your initial investment and the redemption value (the $1,000 in this example). In this case, your position would sell for $1,500 and you would pay a back-end load of $50 ($1,000 X 5%). If the position redemption value was at $900 (less than the initial investment), most funds would apply the back-end load to that value, charging $45.

There are some funds that will charge the fee based on the redemption value, but that is not commonplace. It is always a good idea to read through the prospectus to get a better idea of how fees are structured and exactly what you will pay when it comes time to buy and sell a certain fund.

Non-Load Fees

- Redemption Fee: This is a fee charged when shares are redeemed, similar to a back-end load. Unlike deferred sales charges, however, redemption fees are paid directly to the fund, not the broker. The SEC limits redemption fees to 2%.

- Exchange Fee: A fee charged if a shareholder transfers assets to another fund within the same group of mutual funds.

- Account Fee: This fee is separate from any investments, and is instead charged for maintaining an account with a certain firm. Some may charge, for example, for accounts that have below a certain amount of funding.

- Purchase Fee: Similar to a front-end sales load, purchase fees are paid up front when making an investment, but they instead go to the fund rather than a broker.

- Management Fees: These are paid each year to the fund’s investment advisor from the fund’s assets to compensate for managing the fund’s portfolio.

- Distribution/12b-1 Fees: Also paid out of the fund’s assets, these fees cover distribution expenses and shareholder service expenses. The “12b-1” term comes from an SEC rule of the same title that allows for these fees to be paid.

Why Fees Matter

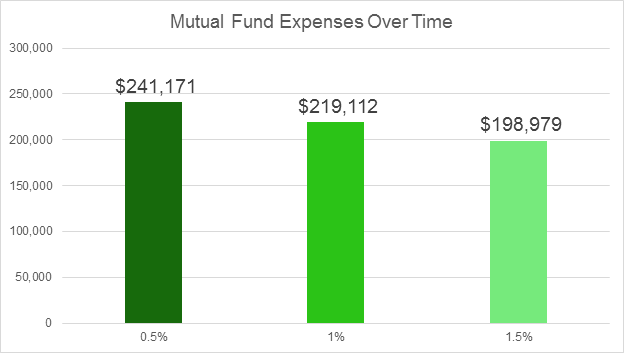

The importance of fee management is best illustrated through a visual example. Let’s take a hypothetical position of $100,000 that earns a 5% return for 20 consecutive years. Now let’s take a look at how total annual operating expenses of a mutual fund can impact returns (note that these do not include fees associated with buying and selling the funds).

Not including expenses, that position will be worth $265,330 at the end of 20 years. But let’s see how that would change with funds that charge 1.5%, 1%, and 0.5% annually.

To help you keep a better tab on your expenses and how they can impact you, FINRA offers a free tool to help you screen funds and understand the expenses that come with each investment.