There are some unwritten rules in personal finance and portfolio construction that nearly everyone seems to follow. Perhaps one of the biggest comes down to bonds and their placement in accounts. Thanks to how interest is taxed, the general idea is a tax-deferred or tax-free account is the best place for them. Taxable accounts should only be used for municipal bonds.

But that widespread thinking may not be the best advice anymore.

It turns out that for many investors, taxable bonds can have a place in taxable accounts and could lead to higher after-tax returns than simply placing them in a tax-deferred account or by using munis. For many investors, going against the grain could pay off.

Bonds & Taxes

There’s a good reason why the pervasive idea about how bonds should be held in tax-sheltered accounts exists. When it comes to Uncle Sam, he has historically treated bonds less favorably than other asset classes.

That’s because interest is not treated the same as capital gains or dividends. At least not on the surface anyway.

Thanks to the Bush-era tax cuts, dividends, and capital gains have been given very favorable tax schemes. The rate works out to be 15% for dividends and long-term capital gains for many investors. This contrasts with bonds, whose interest is taxed at ordinary income rates. That means the interest you receive from a bond can be taxed as high as 37% plus the 3% Obamacare surplus.

That’s a serious tax bite for many investors. So, it’s easy to understand how placing bonds in a 401k or IRA rather than a taxable account can reduce the amount of taxes an investor pays on these IOUs. Moreover, if you are using a taxable account, municipal bonds—with their Federal and potential state/local tax-free interest payments—have been preferred by investors and advisors.

Not So Fast

However, in the modern era, the basic idea that all bonds minus munis must go in a tax-sheltered account is being challenged. And for some investors, it may make sense for them to hold taxable bonds such as Treasuries or corporates in a regular taxable, brokerage account.

That’s because tax brackets are a moving target and just because bonds can be taxed at high rates doesn’t mean they will be. Vanguard has the details.

Generally, investors get hung up on the idea of ordinary income rates and tend to overestimate the actual amount of taxes they pay on their salaries and bond interest. For example, for 2025’s tax bracket bands, a single filer can make up to $100,525 and still be in the 22% bracket. A married couple can make up to $201,050. Those two figures are well above the average American salaries of $146,000 for married couples and $56,065 for single filers. The vast bulk of earners fall within the 10% or 12% brackets.

This reduces the taxes owed on bond interest or at least the perceived taxes on these payouts.

Then there is the bond’s overall interest to consider. Taxable doesn’t always mean fully taxable. Interest income from Treasury bills, notes, and bonds is subjected to federal taxes but is exempt from all state and local income taxes. Conversely, taxable municipal bonds are free from most state taxes, but not federal taxes. This changes the ordinary income equation and doesn’t necessarily make bond placement such a black-and-white decision.

Another consideration is the coupons and interest rates. When bond yields are low, investors are earning less on their investment, which in turn means lower ordinary income rates. As the Fed cuts rates, having bonds in a taxable account makes more sense.

Additionally, those in retirement have special advantages to utilize tax-deferred, tax-free, and taxable accounts to add tax alpha. Old school thinking used to be to deplete taxable accounts first, tax-deferred accounts, and then tax-free Roth accounts when it comes to making retirement withdrawals. However, new analysis has shown that withdrawing from all three each year can help reduce the taxable burden overall. Investors can use their bond interest and tax-deferred withdrawals to stay in lower tax brackets and then pull from a Roth for the rest of their spending needs. This can help make taxable bonds more efficient than previously thought.

Vanguard’s study puts these ideas into practice and underscores how taxable bonds can go into taxable accounts and portfolios to generate more income and higher returns than just using munis, even at higher tax brackets. In their study, assuming a 20% tax on dividends and a 37% tax on ordinary income, including taxable bonds in a taxable portfolio still generates an extra 0.2 basis points in annual return versus conventional portfolio thinking. 1

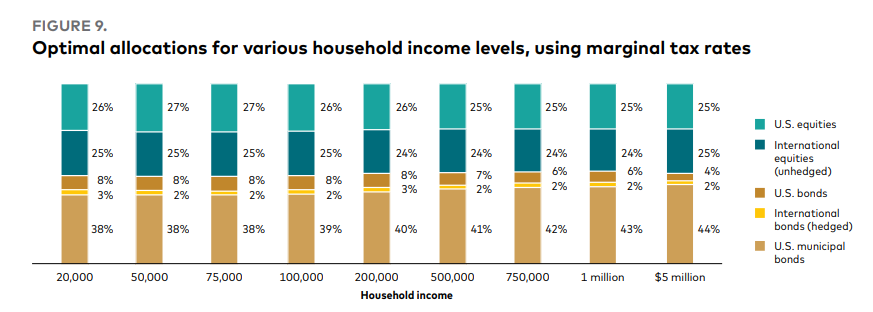

The effect is even more pronounced as investors move down the tax bracket ladder, which is where most of us fall anyway. With that, Vanguard has come up with an optimal allocation for taxable accounts at various income brackets. This includes taxable bonds.

Source: Vanguard

Putting It Into Practice

The reality is taxable bonds aren’t always the boogieman in a taxable account. For most of us, the fact they generate ordinary income is a moot point. What we think we pay in taxes versus what we do pay doesn’t necessarily line up. Moreover, new tools in tax alpha and how we withdraw from our accounts can further reduce the burden that Treasuries, corporate bonds, and other IOUs cause. This leads to higher returns than simply using munis alone or by placing taxable bonds in a tax-sheltered account.

Another thing to consider, which was not included in Vanguard’s study, was the effect of ETFs and the reduction of capital gains. Thanks to their creation-redemption mechanism, ETFs can pass off capital gains. This innovation has further reduced the taxable burden that taxable bonds can have in a regular brokerage account.

Ultimately, investors shouldn’t be scared of taxable bonds in their brokerage accounts.

Popular Bond ETFs

These ETFs were selected based on their size and popularity with investors. They cover a wide range of bond types and are sorted by their one-year total returns, which range from -8% to 9%. They have assets under management of $3.77B to $316B and expenses of 0.03% to 0.40%. They are currently yielding between 3% and 7.7%.

| Ticker | Name | AUM | 1-year Total Ret (%) | Yield (%) | Exp Ratio | Security Type | Actively Managed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USHY | iShares Broad USD High Yield Corporate Bond ETF | $8.99B | 8.9% | 7.4% | 0.08% | ETF | No |

| SJNK | SPDR Bloomberg Short Term High Yield Bond ETF | $3.77B | 8.7% | 7.7% | 0.40% | ETF | No |

| VCSH | Vanguard Short-Term Corporate Bond Index Fund | $42.6B | 5.1% | 3.6% | 0.04% | ETF | No |

| BSV | Vanguard Short-Term Bond Index Fund | $58.8B | 3.9% | 3.0% | 0.04% | ETF | No |

| VCIT | Vanguard Intermediate-Term Corporate Bond Index Fund | $39.6B | 3.6% | 4.2% | 0.04% | ETF | No |

| SHY | iShares 1-3 Year Treasury Bond ETF | $26.3B | 4% | 3.6% | 0.15% | ETF | No |

| BND | Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund | $316B | 1.5% | 3.4% | 0.03% | ETF | No |

| AGG | iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF | $90.4B | 1.4% | 3.6% | 0.03% | ETF | No |

| LQD | iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF | $27.9B | 1% | 4.5% | 0.14% | ETF | No |

| TLT | iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF | $49.8B | -8.0% | 4.0% | 0.15% | ETF | No |

In the end, taxable bonds have a place in taxable accounts for the bulk of investors. The result is they can help generate higher returns while their ‘taxable’ nature is often exaggerated by many people. Investors need to look at their overall bracket and strategies to help reduce taxes via withdrawals before making a decision. There’s a lot more grey area than we think.

Bottom Line

Taxable bonds such as Treasuries and corporate bonds can fit in a taxable account. Simply ignoring them for municipal bonds or placing them solely in a tax-sheltered vehicle may not be the best decision for the long haul. It makes sense to figure out all the possibilities before making a blanket statement.

1 Vanguard (November 2022). Taxable bonds can have a role in tax-aware portfolios